Redux! Obese EVs Generate Massive Plumes of Particulate Carcinogens

Overweight EVs Generate More Toxic Particulates than ICE Cars

Tuco's Child Preface

EVs weigh 1000 to 2000 lbs more than ICE cars to just achieve barely passable range without using the AC or hauling. This is simply because the energy density (Megajoules/kg) of Li batteries is very very low compared to other fuels per the previous article below:

No matter how much EV proponents would like the Laws of Physics to be different, no amount of magical thinking will change our current physical reality with regards to the conservation of matter and energy. The simple mechanics around increased carcinogenic particulate generation by EVs is described below, and in the following articles. I also note that the WSJ just brought up this subject again, but the article is behind a pay-wall.

When a tire rolls down the road, the contact patch instantaneously sticks and unsticks to the road surface, and thus the tire wears via abrasion. The abraded rubber particles that are generated are suspended in the air and are blown by air currents over large areas.

Tire adherence to the road, or traction, is largely influenced rubber tire chemistry and materials, the weight of the car, tire temperatures, and the forces on the tire.

Softer stickier tire compounds wear faster and leave larger more gummy particulate debris, while more common harder higher mileage tire compounds wear more slowly and normally generate vast plumes of fine particulates that comprise of carcinogenic compounds from the tire manufacturing process.

As mentioned, EVs can weigh 1,000 - 2000 lbs or more than ICE cars due to the batteries, and thus they wear out tires 20 to 50 % faster and create more toxic tire dust than an ICE car.

Part 1: The particulate pollution from car tires is nearly 2,000 times worse than that from vehicle exhaust pipes, so lack of EV tailpipe emissions will make no real difference in local air quality

Damian Carrington Environment editor

Almost 2,000 times more particle pollution is produced by tyre wear than is pumped out of the exhausts of modern cars, tests have shown.

The tyre particles pollute air, water and soil and contain a wide range of toxic organic compounds, including known carcinogens, the analysts say, suggesting tyre pollution could rapidly become a major issue for regulators.

Air pollution causes millions of early deaths a year globally. The requirement for better filters has meant particle emissions from tailpipes in developed countries are now much lower in new cars, with those in Europe far below the legal limit. However, the increasing weight of cars means more particles are being thrown off by tyres as they wear on the road.

The tests also revealed that tyres produce more than 1tn ultrafine particles for each kilometre driven, meaning particles smaller than 23 nanometres. These are also emitted from exhausts and are of special concern to health, as their size means they can enter organs via the bloodstream. Particles below 23nm are hard to measure and are not currently regulated in either the EU or US.

“Tyres are rapidly eclipsing the tailpipe as a major source of emissions from vehicles,” said Nick Molden, at Emissions Analytics, the leading independent emissions testing company that did the research. “Tailpipes are now so clean for pollutants that, if you were starting out afresh, you wouldn’t even bother regulating them.”

Molden said an initial estimate of tyre particle emissions prompted the new work. “We came to a bewildering amount of material being released into the environment – 300,000 tonnes of tyre rubber in the UK and US, just from cars and vans every year.”

There are currently no regulations on the wear rate of tyres and little regulation on the chemicals they contain. Emissions Analytics has now determined the chemicals present in 250 different types of tyres, which are usually made from synthetic rubber, derived from crude oil. “There are hundreds and hundreds of chemicals, many of which are carcinogenic,” Molden said. “When you multiply it by the total wear rates, you get to some very staggering figures as to what’s being released.”

The wear rate of different tyre brands varied substantially and the toxic chemical content varied even more, he said, showing low-cost changes were feasible to cut their environmental impact.

“You could do a lot by eliminating the most toxic tyres,” he said. “It’s not about stopping people driving, or having to invent completely different new tyres. If you could eliminate the worst half, and maybe bring them in line with the best in class, you can make a massive difference. But at the moment, there’s no regulatory tool, there’s no surveillance.”

The tests of tyre wear were done on 14 different brands using a Mercedes C-Class driven normally on the road, with some tested over their full lifetime. High-precision scales measured the weight lost by the tyres and a sampling system that collects particles behind the tyres while driving assessed the mass, number and size of particles, down to 6nm. The real-world exhaust emissions were measured across four petrol SUVs, the most popular new cars today, using models from 2019 and 2020.

Used tyres produced 36 milligrams of particles each kilometre, 1,850 times higher than the 0.02 mg/km average from the exhausts. A very aggressive – though legal – driving style sent particle emissions soaring, to 5,760 mg/km.

Far more small particles are produced by the tyres than large ones. This means that while the vast majority of the particles by number are small enough to become airborne and contribute to air pollution, these represent only 11% of the particles by weight. Nonetheless, tyres still produce hundreds of times more airborne particles by weight than the exhausts.

The average weight of all cars has been increasing. But there has been particular debate over whether battery electric vehicles (BEVs), which are heavier than conventional cars and can have greater wheel torque, may lead to more tyre particles being produced. Molden said it would depend on driving style, with gentle EV drivers producing fewer particles than fossil-fuelled cars driven badly, though on average he expected slightly higher tyre particles from BEVs.

Dr James Tate, at the University of Leeds’ Institute for Transport Studies in the UK, said the tyre test results were credible. “But it is very important to note that BEVs are becoming lighter very fast,” he said. “By 2024-25 we expect BEVs and [fossil-fuelled] city cars will have comparable weights. Only high-end, large BEVs with high capacity batteries will weigh more.”

Other recent research has suggested tyre particles are a major source of the microplastics polluting the oceans. A specific chemical used in tyres has been linked to salmon deaths in the US and California proposed a ban this month.

Part 2: Highly carcinogenic tyre toxins give electric car drivers a nasty surprise

Tom Knowles 23 May 2023

Drivers of electric cars are unwittingly releasing more toxic tyre particles into the air than those driving petrol vehicles, experts have warned.

Scientists, analysts and regulators are growing increasingly concerned about the amount of potentially harmful tiny particles coming off tyres, especially those from heavier cars such as electric vehicles, due to the number of toxic petrochemicals that they are made from.

This comes as the Government is attempting to reduce carbon emissions under its “net zero” drive by encoruaging drivers to use electric cars. Motorists with older petrol vehicles in London also face fresh charges to enter Sadiq Khan’s Ultra-low emission zone (Ulez), which is expanding to cover all London boroughs from August.

Ministers have also been considering a “tyre tax” to cut harmful emissions.

However, experts have warned that non-exhaust pollution will rise when more electric cars are on the road.

Professor Roy M. Harrison, at the School of Geography, Earth & Environmental Sciences at the University of Birmingham, said: “The non-exhaust emissions from road traffic in developed countries now exceed the exhaust emissions, so that is a problem. And it's a problem that will get slightly worse as we go into a battery electric fleet and also as traffic volumes probably increase additionally.”

Modern tyres contain around 400 organic compounds, many of which are derived from crude oil. Some of these are highly toxic chemicals such as naphthalene, toluene, and isoprene, as well as heavy metals like zinc and lead.

Every time someone drives, tiny bits of their tyres break away, releasing a range of these toxic chemicals, both in larger pieces and nanoparticles. The bigger pieces will be carried off the road by rain into rivers and sewage, where they may seep into the earth or flow into the sea. The smaller particles will filter into the air and be breathed in by humans and animals, reaching deep into the lungs.

Nick Molden, chief executive at Emissions Analytics, which studies the pollution caused by tyres, said: “We’re going diametrically in the wrong direction at the moment by making our vehicles heavier.

“SUVs and electric cars are shedding an awful lot of tiny but nasty chemicals – some of which are highly carcinogenic – which we’re partly inhaling but are also getting into our water and food.”

Emissions Analytics conducted a test last year that concluded almost 2,000 times more particle pollution is produced by tyre wear than what is pumped out of the exhausts of modern cars.

“If you’re worried about burning fossil fuels in your car engine, you should be as worried about the wear from tyres”, Molden said. “Tailpipe emissions really only affect the air, whereas tyre wear affects air, soil and water.”

This is an issue for the UK and other nations as they move towards having more electric cars. The heavier a vehicle, the greater wear a tyre will face. Electric vehicles weigh an average of 200kg to 300kg more than a petrol car, due to the battery pack. They also need higher torque – the twisting power that launches a car from a standing start – than internal combustion engines, which also puts more pressure on the tyres.

The tyre manufacturer Michelin said conventional tyres wear out around 20pc faster in an electric vehicle, while Goodyear said they can wear out as much as 50pc faster.

In February, researchers at Imperial College London called for more research into the potentially harmful impact of toxic tyre particles on health and the environment. It said six million tonnes of tyre wear particles are released globally each year, and in London alone, 2.6 million vehicles emit around nine thousand tonnes of tyre wear particles annually.

The weight of electric vehicles is already causing concern from some engineers that they will put some multi-storey car parks built in the 1960s and 70s under such pressure they will be at the risk of collapse, The Telegraph reported in April. Government ministers have also urged councils to check how much weight bridges in their area can hold.

This may become even more of an issue in the future as electric cars are set to carry more weight. Rather than battery packs getting lighter as technology advances, electric car manufacturers like Tesla are actually opting for heavier iron-based batteries that do not use the expensive, scarce materials of nickel and cobalt.

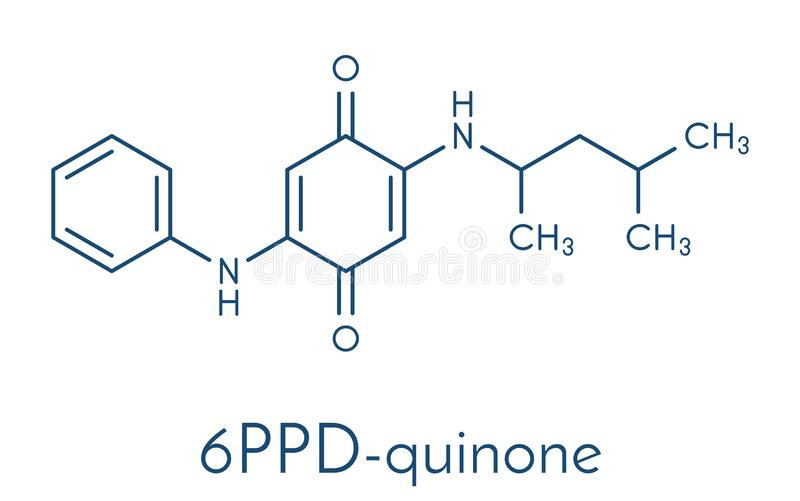

It is not yet clear how harmful tyre particles may be to human health, especially as it can be hard to determine what has come from tyres alone. However, 6PPD, a chemical used almost only in tyres that is included to reduce cracking, has been found to have harmful effects on the environment.

Regulators are starting to acknowledge the issue. In 2025, new EU regulations will introduce a minimum standard for tyre emissions for the first time, while California is considering making tyre manufacturers find alternatives to 6PPD.

Gavin Whitmore, a spokesman for The Tyre Industry Project, an industry-backed research group that counts 11 major tyre makers as members, said: “We remain committed to understanding any potential impacts of tyre and road wear particles and to working with industry and other stakeholders to develop a holistic approach to better understand and promote action on mitigation.”

Part 3: Tyre dust: the ‘stealth pollutant’ that’s becoming a huge threat to ocean life

2022-07-25

For decades, coho salmon returning from the Pacific Ocean to the creeks and streams of Puget Sound in Washington state to spawn were dying in large numbers. No one knew why. Scientists working to solve the mystery of the mass deaths noticed they occurred after heavy rains.

Toxicologists suspected pesticides, as the main creek they studied ran through a golf course. But no evidence of pesticides was found. They ruled out disease, lack of oxygen and chemicals such as metals and hydrocarbons.

The first real breakthrough happened when they tested actual runoff collected from a nearby road and exposed test salmon to it. The fish died within hours.

“The harder step was delving into what could be in that stormwater,” said Jenifer McIntyre, an assistant professor of aquatic toxicology at Washington State University, who has spent 15 years searching for what was killing the coho, an important species in the Pacific north-west.

It was when they tested car tyre particles – a poorly understood yet ubiquitous pollutant – that they knew they were on the right track. Using a parmesan grater atop a drill, they carefully shaved tiny fragments of tyre and soaked them in water.

“When we tested the tyres it killed all the fish,” said McIntyre. From there, they were able to identify the culprit: a toxic chemical known as 6PPD-quinone, the product of the preservative 6PPD, which is added to tyres to stop them breaking down. The pioneering study, published in 2020, has been heralded as critical to our understanding of what some describe as a “stealth pollutant”.

Tyre-wear particles – a mixture of tyre fragments, including synthetic rubbers, fillers and softeners and road surface particles – are considered by environmental scientists to be one of the most significant sources of microplastics in the ocean.

Created during acceleration and braking, they are dispersed from road surfaces by rainfall and wind. The main environmental pathway is from road run-off into storm drains, where they empty into rivers and the sea. They are also released from sewage effluent and from the atmosphere, where they can circulate into the ocean and back again. A 2020 study suggested windblown microplastics are an even bigger source of ocean pollution than rivers.

While it is fiendishly difficult to pin down the exact composition of microplastics, there is plenty of research which points to tyre dust making up a significant portion.

In 2017, a global model by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature estimated tyre wear to be the second largest source of primary microplastics in the ocean, at 28%, after synthetic textile fibres, at 35%.

And, in 2019, a report by scientists across Europe concluded abrasion from car tyres was a large source of microplastics and possibly nanoplastics. While there remains a lack of data on risks to the environment and human health, the scientists concluded that if future emissions remain constant or increase “the ecological risks could be widespread within a century”.

One thing is certain. Tyre-wear particles are ubiquitous. The average tyre loses 4kg over its lifetime. About 6m tonnes of tyre particles are emitted annually and have been found everywhere from the deep sea, to the atmosphere, even in the Arctic and the Antarctic.

And it is only going to get worse. Electric cars will lower tailpipe emissions, but tyre wear is projected to rise, due to heavier vehicles and torque (the rotational force of a car engine). The UK’s air quality group warned in 2019 that dust from tyres and car brakes would continue to pollute the air, rivers and ultimately the sea, even when the fleet has gone electric.

In January, McIntyre’s research team published a new study, which found that 6PPD-quinone was “more toxic than previously calculated” to coho and should be categorised as a “very highly toxic” pollutant for aquatic organisms.

Like any detective, McIntyre hopes her team’s work will prompt others to look backwards, at locally extinct aquatic species, to determine whether 6PPD-quinone may have played a role.

Dr Steve Allen, a specialist in atmospheric microplastics at the Ocean Frontier Institute at Dalhousie University in Canada, described the coho salmon study as “landmark”, because it examined the real-world effects of tyre particles.

The study of microplastic is fast moving but still in its infancy. Fewer than 100 scientific papers about them have been published to date, said Allen, all of them in the last decade.

Siobhan Anderson, the co-founder and chief scientific officer of the Tyre Collective, a group of masters students who designed a device to collect microplastics directly from tyres, calls tyre dust “a stealth pollutant” because few people know about it. “There is very little public awareness,” said Anderson, whose organisation is in talks with Volvo and Seft about development of its device.

“Tyre wear is unique in that it can count as microplastic but it is also air pollution because it’s so small,” she said. “Anything that is 10 microns can be inhaled in our lungs and anything that is 2.5 microns has the potential to pass the membrane barrier,” Anderson said.

Tyre dust particles have been found to be smaller than 23 nanometers (0.02 microns).

Edward Kolodziej, an associate professor at the University of Washington and co-author of the coho study, cites two studies from China showing that tyre dust is an important contributor to urban air pollution. “It’s not just the roadway runoff and stormwater getting into the river that kills the fish, there’s also unknown or poorly characterised chemicals present in these things that are ending up in our lungs.”

Kolodziej is concerned about the big data gaps in our knowledge of the effects of thousands of chemicals in the environment. “As a society, we’re literally making 300,000 chemicals, of which 20,000 to 30,000 are the most commonly used,” he said. “Between 90% and 95% of chemicals have had no assessment of what they do in the environment.”

“All these chemicals are proprietary, confidential business information. When you go and buy a product like a tyre, nobody’s being told about what chemicals are in it.”

Frédérique Mongodin, the senior marine litter policy officer of Seas At Risk, said she is very concerned about the “chemical cocktail” from tyres. “Tyre dust is impossible to control. We are pushing the EU to introduce measures at the design stage.”

The $264bn (£194bn)-a-year tyre industry is countering scientific studies on tyre wear and microplastics with research of its own.

The Tire Industry Project (TIP), a body representing 10 tyre manufacturers including Goodyear, Michelin and Pirelli, has commissioned multiple studies over the last decade, concluding that TRWP (tyre and road wear particles) presents no environmental and health risks.

Gavin Whitmore, the communication manager of TIP, disagrees that tyre wear is a major source of ocean microplastics.

“We’re finding something like 2-5% maximum of TRWP is reaching the ocean,” he said, citing a two-part study published in 2018, commissioned by the European Tyre and Rubber Manufacturers Association, which used the Seine watershed as a case study.

Environmental groups, however, have questioned the independence of this research.

Anne Cécile Rémont, the director of the TIP said that after the coho salmon study, the US Tire Manufacturing Association (USTMA) has been involved in discussions with regulators and stakeholder on “potential alternatives” to 6PPD. A proposal in California, where the loss of coho salmon has significantly affected Indigenous communities, would require tyre makers to consider safer alternatives to 6PPD. USTMA has said it supports the proposal.

Asked if the industry was prepared to be more transparent about the chemicals in tyre wear to speed up research, Rémont said the formula was what gives a manufacturer competitive advantage. “Sharing ingredients is very difficult and complicated,” she said but added that the USTMA is developing a “surrogate test material” for researchers.

But experts are calling for more transparency from the tyre companies. It took decades for scientists to narrow down which chemical was causing the mass die-offs of coho salmon in Washington state.

“Very few people, except manufacturers, know what is in the tyres,” said Allen. “There are thousands upon thousands of chemicals. What happens if two of them get together? When it comes to microplastic, we don’t know what a safe level is and we may have already passed it.”

If you have any doubt to the validity of this article, go to the Indy 500. It's great fun and you will enjoy your day, people watching is half the entertainment. However at the end of the race, you, your cloths, your stuff, will all be covered with a very fine black/brown dust. That is tire dust my friends. If you have ever worked on a heavy truck, it's everywhere.

Seems like a good time to head to a road course and use up another set of Michelin Sport Cup 2s, and make some tire dust.

I still find all of this about tires fascinating. As is the fact that the effect of tires is never reported in the media. Why is that? Must be that it would divert attention from the leftist/Marxist/communist green agenda. Reporting on tire pollution does nothing to promote the end of fossil fuels. We need to transition to wooden tires !!